Considering the Critical Period of Second Language Acquisition

What is the Critical Period of SLA (Second Language Acquisition) Is the Critical Period solely a biological phenomenon, a psychological one, or perhaps a combination? I shall explore these questions with consideration to neuroscience and psychology in this chapter and formulate practical ideas for Second Language (L2) classroom teachers.

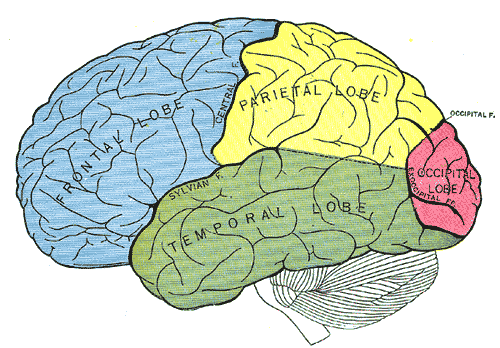

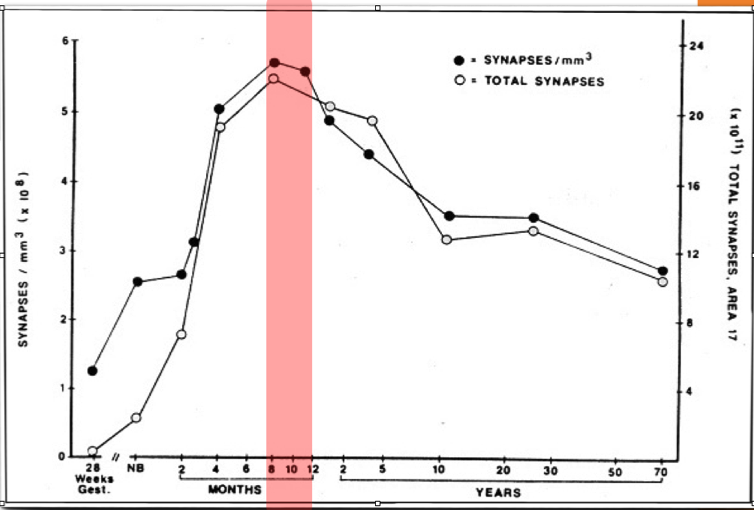

It is a well-documented phenomenon that toddlers grow an excessive number of neurons, only to have them gradually pruned as they grow older. This is called pruning (see above). It seems that this event takes place to ensure that only the most fit neurons are selected to carry on the foundations of the child's cognitive development (Chechik, et al, 1999). Is it possible that our own learning follows a similar pattern during language acquisition? In light of other animals' selective synapse elimination (Knudsen, 2004), it would seem so. We are born with the capability to decipher, learn, and use any human language on the planet. However, we only learn the languages that we actually attempt to negotiate the world with, and in most cases we can only reach a so-called native-like proficiency in any given language if we are exposed to that specific language at a young age. Is there a time when our brains decide to prune sensitivity (synapse elimination) to potential sounds and linguistic patterns that we do not use on a regular basis? Does the brain actually streamline its own linguistic networks in order to focus more attention to (and to therefore raise the amount of usable cognitive processing power for only) the most typical linguistic negotiation patterns? If that is true then it would seem that our brain is marvelously economical in this area as it does away with seemingly needless synapses. Considering the early pruning of 'weak' neurons in toddlers, and combining to it our knowledge of the known functions of myelination (the ability to create more speedy neural network connections by thickening the insulation around our more important neurons' axons) it certainly does seem plausible from a biological perspective that our bodies may benefit from having a Critical Period regarding second language (L2) learning. However, the verdict on the Critical Period is a long-standing debate, with evidence supporting both sides of the issue (Birdsong & Molis, 2001).

The above paragraph shed some light on the plausibility of a Critical Period for L2 from a neuro-biological perspective. Is there a neuro-psychological perspective that can be considered, too? As a child receives input from the world, the brain makes analyzations of the incoming data. This process lays down tracks of cognition that are unique to the given context. These tracks form networks that remain in the brain to help make future decisions when faced with similar contexts (Peabody, 2010). In our massively social existence, most children learn about the world not separated from, but fully integrated with external linguistic input. For instance, most children do not learn about the functionality of crayons, scissors, and paper without at least some linguistic input from parents, peers, and/or teachers. In most cases, children are bombarded with lexical items regarding all aspects of their realm of existence. Because a child's personal understanding of their world is constantly being written and re-written (crafted by and manipulated by) the linguistic input that they happen to receive in concert with each context that they encounter the lexis with, it is my hypothesis that in most circumstances, our own cognitive processes regarding the concepts in our world become reliant on and become largely inseparable from lexical items that have been strongly associated with those experiences because those lexical items were instrumental in the formation of the analysis of those very experiences. They must therefore be an integral part of the cognitive network associated with those experiences. In other words, our lexically based understanding of any given concept is often fused with the non-lexical aspects of cognition regarding the given concept. For example, you cannot think about the word "table" without eventually evoking other lexis on some level connecting to table; you cannot think about "running" without eventually evoking lexis regarding the act of running. From this observation, I claim that at least our upper cognitive processes are typically inseparable from our own first language (L1) lexical items; our understanding of the world is massively fused with our L1 -at least, for monolingual people. Then what of L2 learners? The answer is much more complex. First of all, what is the definition of an L2 learner? The outcomes of such research would vary widely with age and the amount of contextual support -but perhaps more importantly, for such learners, their entire developmental range is what we must ponder, not just isolated instances in time and context (Murphy, 2009). These points are unpacked across the following paragraphs.

According to Fischer's Dynamic Skill Theory (1980, 2006), and my own research in the cognitive development of Japanese students (Murphy, 2009), with proper contextual support, children are capable of cognition at the "abstractions" level beginning around or slightly before the onset of puberty (10-12 or older). Before that level of cognition is the "representations" level. What potential meaning does this have in regard to L2 learning? If a child in even a semi-bilingual/bi-cultural context is given opportunities to manipulate and negotiate the meaning of L2 "representations" (the semantics of concrete items of their world in L2) while they are still developing most of their own basic L1 representations (concrete items) of their own world, they will most likely have authentic intrinsic psycho-social and cultural reasons to acquire the L2 "representations" of that world as they experience them in tandem with their developing L1 "representations". This will likely continue as long as they are in an L2 rich context that provides them with meaningful L2 input. However, if a child is put in an L2 rich context when the child has already reached 10-12 years of age or older and has consequently become capable of realizing cognition at the level of "abstractions" (and therefore has naturally lost some of the novel focus on building "representation" level pragmatic neural connections), he/she may no longer have strong intrinsic motivation to acquire the L2 as a fundamental strand for unraveling the mysteries their world, unfortunately making the L2 forever a foreign/alien aspect to the child.

Even considering the intricacies and dynamism of the minor daily ups and downs in cognitive skill development, or microdevelopment (Schwartz & Fischer, 2005), I hypothesize that when a child grows accustomed to cognitive functioning at the abstractions levels, lower level cognition could literally seem like child's play in many instances, and therefore not be regarded as part of a very enticing learning experience. This point is highly note-worthy. Moreover, I believe this negativity toward lower level cognitive activities gets stronger with adults, which is why although microdevelopment is very much a reality even for adult language learning, adult language learners are seldom seen playing with wooden ABC blocks and/or seen molding clay animals in language classrooms, even though such activities have the potential of being beneficial (Call, 1999; Hirsh-Pasek, 2006). However unfortunate it may be, it would seem that most adults are too proud to actively and openly regress to lower states of cognition even though it could be beneficial for their L2 acquisition. Not only might adults resent what may seem like child's play, perhaps much more importantly, they may have difficulty with the process of "re-perceiving" the world around them. I believe this second barrier is more difficult to overcome than the first one. Psychologically, having to re-perceive the world could be unnerving and perhaps even devastating for some adults. From my own experience, I can say that many adults, somewhat understandably, don't seem to feel comfortable about actively engaging in the deconstruction of the very foundations of their own worldly (and in some cases, spiritual) enlightenment that has been built up throughout their lifetime in tandem with their L1s -simply for the sake a acquiring an L2 at a native-like level. I see this as a major psychological impediment that is perhaps the key component of the Critical Period issue.

Although biological and psychological aspects work together to form the so-called Critical Period for L2 learning, I see the psychological side to be more of a significant issue for teachers because I hypothesize that if the psychological issues of the Critical Period are skillfully tended to, then the biological issues may to some extent (due to our remarkable brain plasticity) take care of themselves. I further hypothesize that the opposite will not hold true - a brain that is somehow biologically still open to native-like L2 acquisition after puberty will not automatically provide the learner with the psychological plasticity to be more open to the notion of completely re-perceiving their world for the sake of L2 acquisition. For these reasons I believe teachers should focus on the positive aspects of effective pedagogy in the L2 classrooms leading toward affects in brain plasticity and positive change rather than dwelling on the fact that there may be a damning biological issue at play regarding L2 acquisition timing.

So, how can this knowledge be used in the L2 classroom? Since adults (both students and teachers) somewhat automatically attempt to tackle language learning with prefrontal analyzation in conjunction with working memory, yet often do not employ the faculties of the amygdala and hippocampus enough through emotion rendering activities, a simple yet potent suggestion I would like to make is to put less emphasis on the computer-like rote memorizations and/or prefrontal organizations and analyzations (such as is the case with Grammar-Translation and "Presentation, Practice, Production [PPP]" style pedagogies), but instead put more emphasis on "play" and real-time "negotiation of meaning" in conversations. In short, I recommend activities that involve games, game-like play, and fruitful discussions that elicit real emotions concerning egocentric matters. In this way, adults may be able to run though stages of microdevelopment (working on lower levels of cognitive development) without even noticing they are doing so, therefore achieving the goals without bruising their pride.

In this chapter, I have briefly examined the Critical Period of SLA from a biological and psychological point of view. I came to the conclusion that, it may be more beneficial to downplay the possible negative biological aspects of the Critical Period, and to focus efforts on the positive aspects of brain plasticity. I believe brain plasticity in L2 contexts may be positively affected by pedagogy inclusive of game play and egocentric discussions that connect with real emotions in the classroom rather than non-personal, overly analytical methodologies, even though adults may initially show a stronger preference for the latter.